It is common practice to use matrices to represent transformations of a vector into another vector. Here, we discuss another quantity, known as a tensor, that achieves the same purpose. We generally denote tensors by uppercase boldfaced symbols, such as ![]() , and symbolize the transformation of a vector

, and symbolize the transformation of a vector ![]() by

by ![]() to a vector

to a vector ![]() as

as

(1) ![]()

The advantages of using tensors are that they are often far more compact than matrices, they are easier to differentiate, and their components transform transparently under changes of bases. The latter feature is very useful when interpreting results in rigid-body kinematics. Consequently, we choose to employ a tensor notation throughout this site for many of the developments we present. This page is intended as both a brief introduction to and review of tensors and their properties. The material provided in the forthcoming sections is standard background for courses in continuum mechanics, and, as such, the primary sources of this information are works by Casey [1, 2], Chadwick [3], and Gurtin [4].

Contents

Preliminaries

To lay the foundation for our upcoming exposition on tensors, we begin with a brief discussion of basis vectors and define two symbols that prove useful in subsequent sections.

Basis vectors

Euclidean three-space is denoted by ![]() . For this space, we define a fixed, right-handed orthonormal basis

. For this space, we define a fixed, right-handed orthonormal basis ![]() . By orthonormal, we mean that for any set of vectors

. By orthonormal, we mean that for any set of vectors ![]() , the dot products

, the dot products ![]() when

when ![]() and

and ![]() when

when ![]() . Unless indicated otherwise, lowercase italic Latin indices such as

. Unless indicated otherwise, lowercase italic Latin indices such as ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() range from 1 to 3. If

range from 1 to 3. If ![]() is right-handed, then the following scalar triple product is positive:

is right-handed, then the following scalar triple product is positive:

(2) ![]()

We also make use of another right-handed orthonormal basis, ![]() , that is not necessarily fixed.

, that is not necessarily fixed.

The Kronecker delta

We use copious amounts of dot products, so it is convenient to define the Kronecker delta ![]() :

:

(3) ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{equation*}\delta_{ij} =\left\{ \begin{array}{c}1 \quad i = j,\\[0.075in]0 \quad i \ne j.\end{array}\right. \end{equation*}](https://rotations.berkeley.edu/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-f34d9904d598f2cbc6c6372de0479d85_l3.png)

Clearly,

(4) ![]()

The alternating symbol

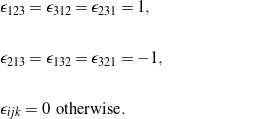

We also occasionally make use of the alternating (or Levi-Civita) symbol ![]() , which is defined such that

, which is defined such that

(5)

In words, ![]() if

if ![]() is an even permutation of 1, 2, and 3;

is an even permutation of 1, 2, and 3; ![]() if

if ![]() is an odd permutation of 1, 2, and 3; and

is an odd permutation of 1, 2, and 3; and ![]() if either

if either ![]() ,

, ![]() , or

, or ![]() . We also note that

. We also note that

(6) ![]()

which is simple to verify by using the definition of the scalar triple product.

The tensor product of two vectors

The tensor (or cross-bun) product of any two vectors ![]() and

and ![]() in

in ![]() is defined by

is defined by

(7) ![]()

where ![]() is any vector in

is any vector in ![]() . That is,

. That is, ![]() projects

projects ![]() onto

onto ![]() and multiplies the resulting scalar by

and multiplies the resulting scalar by ![]() . Put another way,

. Put another way, ![]() transforms

transforms ![]() into a vector that is parallel to

into a vector that is parallel to ![]() . A related tensor product is defined as follows:

. A related tensor product is defined as follows:

(8) ![]()

In either case, ![]() performs a linear transformation of

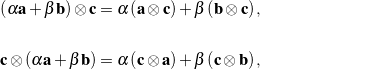

performs a linear transformation of ![]() that it acts on. The tensor product has the following useful properties:

that it acts on. The tensor product has the following useful properties:

(9)

where ![]() and

and ![]() are any two scalars. To prove these identities, one merely shows that the left- and right-hand sides provide the same transformation of any vector

are any two scalars. To prove these identities, one merely shows that the left- and right-hand sides provide the same transformation of any vector ![]() in

in ![]() .

.

Second-order tensors

A second-order tensor ![]() is a linear transformation of

is a linear transformation of ![]() into itself. That is, for any two vectors

into itself. That is, for any two vectors ![]() and

and ![]() and any two scalars

and any two scalars ![]() and

and ![]() ,

,

(10) ![]()

where ![]() and

and ![]() are both vectors in

are both vectors in ![]() . The tensor

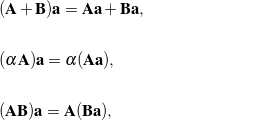

. The tensor ![]() is a simple example of a second-order tensor. It is standard to define the following composition rules for second-order tensors:

is a simple example of a second-order tensor. It is standard to define the following composition rules for second-order tensors:

(11)

where ![]() and

and ![]() are any second-order tensors. To check if two second-order tensors

are any second-order tensors. To check if two second-order tensors ![]() and

and ![]() are identical, it suffices to show that

are identical, it suffices to show that ![]() for any

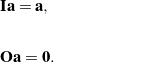

for any ![]() . We also define the identity tensor

. We also define the identity tensor ![]() and the zero tensor

and the zero tensor ![]() :

:

(12)

Representations

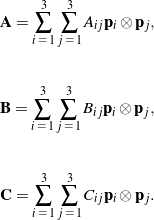

It is convenient at this stage to establish the following representation for any second-order tensor ![]() :

:

(13) ![]()

where

(14) ![]()

are the components of ![]() relative to the basis

relative to the basis ![]() . The order of the indices

. The order of the indices ![]() and

and ![]() is important. Initially, it is convenient to interpret a tensor using the representation

is important. Initially, it is convenient to interpret a tensor using the representation

(15) ![]()

for which

(16) ![]()

In this light, ![]() transforms

transforms ![]() into

into ![]() . Hence, if we know what

. Hence, if we know what ![]() does to three orthonormal vectors, then we can write its representation immediately. To arrive at representation (13), we examine the action of a second-order tensor

does to three orthonormal vectors, then we can write its representation immediately. To arrive at representation (13), we examine the action of a second-order tensor ![]() on any vector

on any vector ![]() :

:

(17) ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{eqnarray*}{\bf A}{\bf b} \!\!\!\!\! &=& \!\!\!\!\! \sum_{i \, \, = \, 1}^3{\bf A} (b_i {\bf p}_i)= \sum_{i \, \, = \, 1}^3 b_i ({\bf A} {\bf p}_i)= \sum_{i \, \, = \, 1}^3 b_i \left(\sum_{j \, \, = \, 1}^3 A_{ji}{\bf p}_j \right)= \sum_{i \, \, = \, 1}^3 \sum_{j \, \, = \, 1}^3 b_i \left( A_{ji}{\bf p}_j \right)= \left(\sum_{i \, \, = \, 1}^3 \sum_{j \, \, = \, 1}^3 A_{ji}{\bf p}_j\otimes{\bf p}_i \right) \left( \sum_{k \, \, = \, 1}^3 b_k{\bf p}_k \right) \hspace{1in} \scalebox{0.001}{\textrm{\textcolor{white}{.}}}\\\\[0.10in]&=& \!\!\!\!\! \left( \sum_{i \, \, = \, 1}^3 \sum_{j \, \, = \, 1}^3 A_{ji}{\bf p}_j\otimes{\bf p}_i \right) {\bf b} ,\end{eqnarray*}](https://rotations.berkeley.edu/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-f3222afa97f0231d7924beb1d03aa2cc_l3.png)

where we used the definition of the tensor product of two vectors in the next-to-last step. Thus, we infer that ![]() has the representation given by (13). We can use this representation to establish expressions for the transformation induced by

has the representation given by (13). We can use this representation to establish expressions for the transformation induced by ![]() . To proceed, define

. To proceed, define ![]() , in which case, from (17),

, in which case, from (17),

(18) ![]()

The components ![]() of

of ![]() are then given by

are then given by

(19) ![]()

When expressed in matrix notation, (19) has a familiar form:

(20) ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{equation*}\left[ \begin{array}{c c c}c_{1} \\c_{2} \\c_{3} \\\end{array} \right] =\left[ \begin{array}{c c c}A_{11} & A_{12} & A_{13} \\A_{21} & A_{22} & A_{23} \\A_{31} & A_{32} & A_{33} \\\end{array} \right]\left[ \begin{array}{c c c}b_{1} \\b_{2} \\b_{3} \\\end{array} \right].\end{equation*}](https://rotations.berkeley.edu/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-87cbc6a755ce82900094e4eea458a366_l3.png)

Note that (20) implies that the identity tensor has the representation ![]() .

.

The product of two second-order tensors

We now turn to the product of two second-order tensors ![]() and

and ![]() . The product

. The product ![]() is defined here to be a second-order tensor

is defined here to be a second-order tensor ![]() . First, let

. First, let

(21)

We then solve the equations

(22) ![]()

for the nine components of ![]() , where

, where ![]() is any vector. Using the arbitrariness of

is any vector. Using the arbitrariness of ![]() , we conclude that the components of the three tensors, which are all expressed in the same basis, are related by

, we conclude that the components of the three tensors, which are all expressed in the same basis, are related by

(23) ![]()

This result is identical to that for matrix multiplication. Indeed, if we define three matrices whose components are ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() , then we find the representation

, then we find the representation

(24) ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{equation*}\left[ \begin{array}{c c c }C_{11} & C_{12} & C_{13} \\C_{21} & C_{22} & C_{23} \\C_{31} & C_{32} & C_{33}\end{array} \right] =\left[ \begin{array}{c c c }A_{11} & A_{12} & A_{13} \\A_{21} & A_{22} & A_{23} \\A_{31} & A_{32} & A_{33}\end{array} \right]\left[ \begin{array}{c c c }B_{11} & B_{12} & B_{13} \\B_{21} & B_{22} & B_{23} \\B_{31} & B_{32} & B_{33}\end{array} \right]. \hspace{1in} \scalebox{0.001}{\textrm{\textcolor{white}{.}}}\end{equation*}](https://rotations.berkeley.edu/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-bc1366f9bf41c8634bfd32807ca0ed8f_l3.png)

It is straightforward to establish a similar representation for the product ![]() . Finally, consider the product of two second-order tensors

. Finally, consider the product of two second-order tensors ![]() and

and ![]() :

:

(25) ![]()

This result is the simplest way to remember how to multiply two second-order tensors.

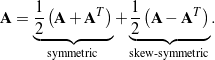

Symmetric and skew-symmetric tensors

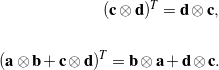

The transpose ![]() of a second-order tensor

of a second-order tensor ![]() is defined such that

is defined such that

(26) ![]()

for any two vectors ![]() and

and ![]() . If we consider the second-order tensor

. If we consider the second-order tensor ![]() , then we can use definition (26) to show that

, then we can use definition (26) to show that

(27)

Given any two second-order tensors ![]() and

and ![]() , it can be shown that the transpose

, it can be shown that the transpose ![]() . If

. If ![]() , then

, then ![]() is said to be symmetric. On the other hand,

is said to be symmetric. On the other hand, ![]() is skew-symmetric if

is skew-symmetric if ![]() . Using the representation (13) for

. Using the representation (13) for ![]() and the identity (27)1, we find that the tensor components

and the identity (27)1, we find that the tensor components ![]() when

when ![]() is symmetric and

is symmetric and ![]() when

when ![]() is skew-symmetric. These results imply that

is skew-symmetric. These results imply that ![]() has six independent components when it is symmetric but only three independent components when skew-symmetric. Lastly, it is always possible to decompose any second-order tensor

has six independent components when it is symmetric but only three independent components when skew-symmetric. Lastly, it is always possible to decompose any second-order tensor ![]() into the sum of a symmetric tensor and a skew-symmetric tensor:

into the sum of a symmetric tensor and a skew-symmetric tensor:

(28)

Invariants

There are three scalar quantities associated with a second-order tensor that are independent of the right-handed orthonormal basis used for ![]() . Because these quantities are independent of the basis, they are known as the (principal) invariants of a second-order tensor. Given a second-order tensor

. Because these quantities are independent of the basis, they are known as the (principal) invariants of a second-order tensor. Given a second-order tensor ![]() , the invariants

, the invariants ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() of

of ![]() are defined as

are defined as

(29) ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{eqnarray*}&& I_{\bf A}[{\bf a}, \, {\bf b}, \, {\bf c}] =[{\bf A}{\bf a}, \, {\bf b}, \, {\bf c}] +[{\bf a}, \, {\bf A}{\bf b}, \, {\bf c}] +[{\bf a}, \, {\bf b}, \, {\bf A}{\bf c}] ,\\\\&& II_{\bf A}[{\bf a}, \, {\bf b}, \, {\bf c}] =\mbox{[}{\bf a}, \, {\bf A}{\bf b}, \, {\bf A}{\bf c}] +\mbox{[}{\bf A}{\bf a}, \, {\bf b}, \, {\bf A}{\bf c}] +\mbox{[}{\bf A}{\bf a}, \, {\bf A}{\bf b}, \, {\bf c}] , \\\\&& III_{\bf A}[{\bf a}, \, {\bf b}, \, {\bf c}] =\mbox{[}{\bf A}{\bf a}, \, {\bf A}{\bf b}, \, {\bf A}{\bf c}] ,\end{eqnarray*}](https://rotations.berkeley.edu/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-c85ebd453a18ee10b5ff483e5cd65fd2_l3.png)

where ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() are any three vectors. The first invariant

are any three vectors. The first invariant ![]() is known as the trace of a tensor

is known as the trace of a tensor ![]() , and the third invariant

, and the third invariant ![]() is known as the determinant of

is known as the determinant of ![]() :

:

(30)

Suppose we represent ![]() in terms of a right-handed orthonormal basis

in terms of a right-handed orthonormal basis ![]() in

in ![]() , such as in representation (13). If we take

, such as in representation (13). If we take ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() , then

, then

(31) ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{eqnarray*}&& [{\bf p}_1, \, {\bf p}_2, \, {\bf p}_3] = 1,\\\\[0.10in]&& \mbox{[}{\bf A}{\bf p}_1, \, {\bf p}_2, \, {\bf p}_3] +[{\bf p}_1, \, {\bf A}{\bf p}_2, \, {\bf p}_3] +[{\bf p}_1, \, {\bf p}_2, \, {\bf A}{\bf p}_3] =\sum_{i \, \, = \, 1}^3 ({\bf A}{\bf p}_i)\cdot{\bf p}_i = A_{11} + A_{22} + A_{33}, \hspace{1in} \scalebox{0.001}{\textrm{\textcolor{white}{.}}}\\\\\\&& \mbox{[}{\bf A}{\bf p}_1, \, {\bf A}{\bf p}_2, \, {\bf A}{\bf p}_3] =\sum_{i \, \, = \, 1}^3 \sum_{j \, \, = \, 1}^3 \sum_{k \, \, = \, 1}^3 \altepsilon_{ijk} A_{i1}A_{j2}A_{k3} =\det \left(\left[ \begin{array}{c c c }A_{11} & A_{12} & A_{13} \\A_{21} & A_{22} & A_{23} \\A_{31} & A_{32} & A_{33}\end{array} \right] \right) .\end{eqnarray*}](https://rotations.berkeley.edu/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-6d2a72100de3728ac6d2d426ee4c9bb4_l3.png)

Consequently, the trace of ![]() is given by

is given by

(32) ![]()

A similar result holds for the trace of a matrix. We also note the related result ![]() . In addition, we find that the determinant of

. In addition, we find that the determinant of ![]() can be computed using a familiar matrix representation:

can be computed using a familiar matrix representation:

(33) ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{equation*}\det({\bf A}) =\sum_{i \, \, = \, 1}^3 \sum_{j \, \, = \, 1}^3 \sum_{k \, \, = \, 1}^3 \altepsilon_{ijk} A_{i1}A_{j2}A_{k3} =\det \left(\left[ \begin{array}{c c c }A_{11} & A_{12} & A_{13} \\A_{21} & A_{22} & A_{23} \\A_{31} & A_{32} & A_{33}\end{array} \right]\right). \hspace{1in} \scalebox{0.001}{\textrm{\textcolor{white}{.}}}\end{equation*}](https://rotations.berkeley.edu/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-e30637cd321fe1484393a09ccb82ae2f_l3.png)

Inverses and adjugates

The inverse ![]() of a second-order tensor

of a second-order tensor ![]() is the tensor that satisfies

is the tensor that satisfies

(34) ![]()

For the inverse of ![]() to exist, its determinant

to exist, its determinant ![]() . Taking the transpose of (34), we find that the inverse of the transpose of

. Taking the transpose of (34), we find that the inverse of the transpose of ![]() is the transpose of the inverse. The adjugate

is the transpose of the inverse. The adjugate ![]() satisfies

satisfies

(35) ![]()

for any two vectors ![]() and

and ![]() . If

. If ![]() is invertible, then (35) yields a relationship between

is invertible, then (35) yields a relationship between ![]() and

and ![]() :

:

(36) ![]()

Eigenvalues and eigenvectors

The eigenvalues (or characteristic values, or principal values) of a second-order tensor ![]() are defined as the roots

are defined as the roots ![]() of the characteristic equation

of the characteristic equation

(37) ![]()

The three roots of this equation are denoted by ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . On expanding the characteristic equation (37), we find that

. On expanding the characteristic equation (37), we find that

(38) ![]()

where

(39) ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{eqnarray*}&& I_{\bf A} = \mbox{tr}({\bf A}) = \lambda_1 + \lambda_2 + \lambda_3 ,\\\\[0.15in]&& II_{\bf A} = \frac{1}{2}(\mbox{tr}({\bf A})^2 - \mbox{tr}({\bf A}^2) ) = \lambda_1\lambda_2 + \lambda_2\lambda_3 + \lambda_1\lambda_3 ,\\\\[0.15in]&& III_{\bf A} = \det({\bf A}) = \lambda_1\lambda_2\lambda_3 .\end{eqnarray*}](https://rotations.berkeley.edu/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-53b0d7b7983735ede8be3d2e85ba0a8e_l3.png)

The corresponding eigenvectors (or characteristic directions, or principal directions) of ![]() are the vectors

are the vectors ![]() that satisfy

that satisfy

(40) ![]()

A second-order tensor has three eigenvectors, one associated with each eigenvalue. To determine these eigenvectors, we express (40), with the help of (20), in matrix-vector form and then use standard solution techniques from linear algebra. Note that the eigenvectors are unique up to a multiplicative constant.

Proper-orthogonal tensors

A second-order tensor ![]() is said to be orthogonal if

is said to be orthogonal if ![]() . That is, the transpose of an orthogonal tensor is its inverse. It also follows that

. That is, the transpose of an orthogonal tensor is its inverse. It also follows that ![]() . An orthogonal tensor

. An orthogonal tensor ![]() has the unique property that

has the unique property that ![]() for any vector

for any vector ![]() , and so it preserves the length of the vector that it transforms. A tensor

, and so it preserves the length of the vector that it transforms. A tensor ![]() is proper-orthogonal if it is orthogonal and its determinant

is proper-orthogonal if it is orthogonal and its determinant ![]() specifically. Thus, proper-orthogonal second-order tensors are a subclass of the second-order orthogonal tensors.

specifically. Thus, proper-orthogonal second-order tensors are a subclass of the second-order orthogonal tensors.

Positive-definite tensors

A second-order tensor ![]() is said to be positive-definite if

is said to be positive-definite if ![]() for any vector

for any vector ![]() and

and ![]() if, and only if,

if, and only if, ![]() . A consequence of this definition is that a skew-symmetric second-order tensor can never be positive-definite. If

. A consequence of this definition is that a skew-symmetric second-order tensor can never be positive-definite. If ![]() is positive-definite, then all three of its eigenvalues are positive and, furthermore, the tensor has the representation

is positive-definite, then all three of its eigenvalues are positive and, furthermore, the tensor has the representation

(41) ![]()

where ![]() and

and ![]() are the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of

are the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of ![]() , respectively. This representation is often known as the spectral decomposition.

, respectively. This representation is often known as the spectral decomposition.

Third-order tensors

A third-order tensor transforms vectors into second-order tensors and may transform second-order tensors into vectors. With respect to a right-handed orthonormal basis ![]() , any third-order tensor

, any third-order tensor ![]() can be represented as

can be represented as

(42) ![]()

and we define the following two tensor products:

(43) ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{eqnarray*}&& ({\bf a}\otimes{\bf b}\otimes{\bf c})\left[{\bf d}\otimes{\bf e}\right] =({\bf b}\cdot{\bf d})({\bf c}\cdot{\bf e}) {\bf a}, \\\\&& ({\bf a}\otimes{\bf b}\otimes{\bf c}){\bf d} = ({\bf c}\cdot{\bf d}) ({\bf a}\otimes{\bf b}).\end{eqnarray*}](https://rotations.berkeley.edu/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-529710423544fb595a660b0f6fc87f13_l3.png)

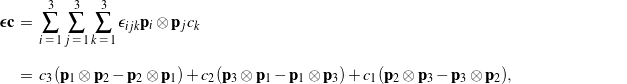

Note the presence of the brackets ![]() in (43)1. The main example of a third-order tensor we use throughout this site is the alternator

in (43)1. The main example of a third-order tensor we use throughout this site is the alternator ![]() :

:

(44) ![]()

This tensor has some useful features. First, if ![]() is a symmetric second-order tensor, then

is a symmetric second-order tensor, then ![]() . Second, for any vector

. Second, for any vector ![]() ,

,

(45)

which is a skew-symmetric second-order tensor. Thus, ![]() can be used to transform a vector into a second-order skew-symmetric tensor and transform the skew-symmetric part of a second-order tensor into a vector.

can be used to transform a vector into a second-order skew-symmetric tensor and transform the skew-symmetric part of a second-order tensor into a vector.

Axial vectors

The fact that the third-order alternating tensor ![]() acts on a vector to produce a skew-symmetric second-order tensor enables us to define a skew-symmetric tensor

acts on a vector to produce a skew-symmetric second-order tensor enables us to define a skew-symmetric tensor ![]() for every vector

for every vector ![]() , and vice versa:

, and vice versa:

(46) ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{eqnarray*}&& {\bf C} = - {\bepsilon}{\bf c},\\\\[0.10in]&& {\bf c} = - \frac{1}{2}{\bepsilon}\left[{\bf C}\right]. \end{eqnarray*}](https://rotations.berkeley.edu/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-25cfa8afc3c62522795de0b0babbb20e_l3.png)

The vector ![]() is known as the axial vector of

is known as the axial vector of ![]() . Notice that if

. Notice that if ![]() has the representation

has the representation

(47) ![]()

then, with the help of (43)1, its axial vector

(48) ![]()

We also note the important result

(49) ![]()

for any other vector ![]() . This identity allows us to replace cross products with tensor products, and vice versa. We often express the relationship between a skew-symmetric tensor

. This identity allows us to replace cross products with tensor products, and vice versa. We often express the relationship between a skew-symmetric tensor ![]() and its axial vector

and its axial vector ![]() without explicit mention of the alternator

without explicit mention of the alternator ![]() :

:

(50)

Differentiation of tensors

One often encounters derivatives of tensors. Suppose a second-order tensor ![]() has the representation (13), where the tensor components

has the representation (13), where the tensor components ![]() and the basis vectors

and the basis vectors ![]() are functions of time. The time derivative of

are functions of time. The time derivative of ![]() is defined as

is defined as

(51) ![]()

Notice that we differentiate both the components and the basis vectors. We can also define a chain rule and product rules. If the tensors ![]() and

and ![]() and the vector

and the vector ![]() , then

, then

(52) ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{eqnarray*}&& \dot{\bf A} = \frac{\partial {\bf A}}{\partial q} \dot{q},\\\\[0.10in]&& \dot{ \overline{ {\bf A}{\bf B} } } = \dot{\bf A}{\bf B} + {\bf A}\dot{\bf B}, \\\\&& \dot{ \overline{ {\bf A}{\bf c} } } = \dot{\bf A}{\bf c} + {\bf A}\dot{\bf c}.\end{eqnarray*}](https://rotations.berkeley.edu/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-d9ba6ae4f68fc802dd92f8d552199f81_l3.png)

Now, consider a function ![]() . The derivative of this function with respect to

. The derivative of this function with respect to ![]() is defined to be the second-order tensor

is defined to be the second-order tensor

(53) ![]()

In addition, if the basis vectors ![]() are constant, then

are constant, then

(54) ![]()

References

- Casey, J., A treatment of rigid body dynamics, ASME Journal of Applied Mechanics 50(4a) 905–907 and 51 227 (1983).

- Casey, J., On the advantages of a geometrical viewpoint in the derivation of Lagrange’s equations for a rigid continuum, Zeitschrift für angewandte Mathematik und Physik 46 S805–S847 (1995).

- Chadwick, P., Continuum Mechanics: Concise Theory and Problems, Dover Publications, New York (1999). Reprint of the George Allen & Unwin Ltd., London, 1976 edition.

- Gurtin, M. E., An Introduction to Continuum Mechanics, Academic Press, New York (1981).